Blue Spur – From Gold Rush to Today

Blue Spur Gold

Blue Spur – From Gold Rush to Today

The name Blue Spur is said to come from the distinctive colour of the “wash dirt” found in the area — a heavy blue sandstone wash that miners believed signalled the presence of gold. This association between blue clay and good gold returns made Blue Spur a place of great promise during the gold rush years.

The Early Gold Rush

When the West Coast was proclaimed a sustainable gold field in March 1864, prospectors poured into the province from Central Otago, Bendigo (Australia), and other key goldfields. Their first focus was the 40-mile stretch of country between the Grey and Totara Rivers, seeking the richest opportunities. Hokitika became the primary port of entry for this new wave of miners, although Greymouth also began receiving ships and grew in importance.

Travel inland was extremely challenging. The dense bush and powerful rivers forced early prospectors to follow beaches, riverbeds, and creeks, shaping where the first claims were worked. After gold was discovered at Greenstone Creek, new strikes soon followed — most notably in November 1864 around the Waimea Stream (known then as Six Mile). The Waimea rush produced excellent returns and cemented the future of the gold rush on the Coast. By early 1865, around 4,000 miners were working the Waimea. The sheer numbers put pressure on authorities to open more ground, and many prospectors began exploring inland areas despite the difficult terrain.

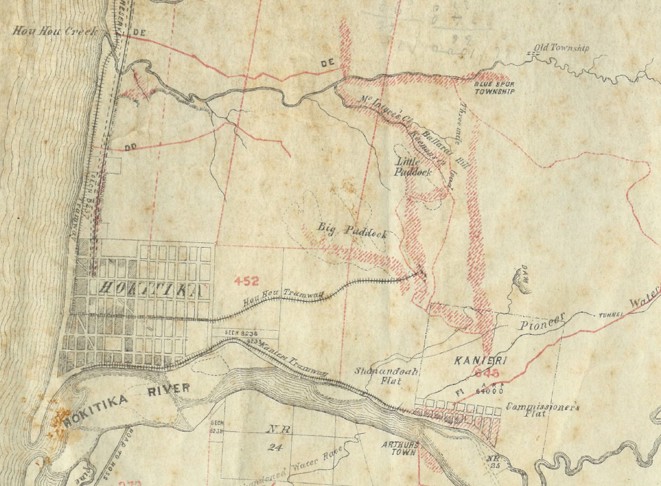

A second major rush began in April 1865 at Kaniere, just three miles upstream from Hokitika. Several thousand miners quickly gravitated to the diggings, relieving congestion on the Waimea.

The Discovery of Blue Spur

Northwest of Kaniere lay a broad tableland of old uplifted black-sand beach terraces that would become known as Blue Spur. Early prospecting occurred there from late 1864, though in small numbers because of the difficulty of access. Miners cut rough horse tracks into the area and attempted to keep their finds quiet to prevent a rush.

In April 1865, the first significant Blue Spur rush began at the headwaters of Ho Ho Creek (also called Hou Hou, Hau Hau, or Three Mile Creek), which flows from the Blue Spur Range. Around 1,500 men rushed to trace the Ho-Ho Lead, a gold-bearing layer that ran south-southwest through the range and terminated at what became known as Big Paddock. Over the next ten months, nearly every ridge of the Blue Spur Range was shafted or tunnelled.

By February 1866, another major find was made in German Gully, a northern tributary of the Ho Ho Creek, sparking a second rush of about 1,500 miners. By mid-1866, the population of the Ho Ho field was estimated at 2,500, and the West Coast Times reported that “considerable numbers of miners are well satisfied with [their] returns.”

Eventually, five distinct leads were discovered, all remnants of an ancient black-sand foreshore: Piccaninny, Madmans, New Chums, Champagne, and Blacksmiths. Early methods of extraction were labour-intensive: miners tunnelled and shafted into the leads, shovelling material into cradles to wash out the gold. The “hopperings” (the concentrate) were burned in kilns, then crushed and recradled — an inefficient process that lost much gold. Later, crushing machinery was introduced, and sluicing became the preferred technique.

Townships and Communities

At its peak, Big Paddock supported a bustling township of 40 stores, two hotels, four butchers, four bootmakers, and a slaughter yard serving a population of 2,500. Little Paddock, northwest of Big Paddock, grew into another settlement with 30 stores and a sea of diggers’ tents.

Blue Spur Township itself lay northeast of Little Paddock. No known images survive, but records describe a school (opened 1875 with 50 pupils), the Exchange Hotel, accommodation houses, stores, a postal service, butcher, baker, and a community hall for gatherings, church services, and meetings. The school closed in 1928, with children thereafter transported daily to Hokitika.

These communities were often short-lived. Buildings were dismantled and moved as new leads opened up. At one point in the mid-1860s there were 11 small townships scattered around Blue Spur, including All Nation Hill, Ballarat Hill, Hau Hau, Little Paddock, and Three Mile.

Earnings were good: miners could expect £7–£20 per week — a strong income for the time. The Blue Spur rush peaked in late 1866, giving Hokitika’s economy a vital boost just as the Kaniere diggings began to slow. By 1867, however, the main rush had faded, and reworking of tailings replaced the opening of fresh ground.

Access and Technology

In 1867, a horse-drawn tramway was built between Hokitika and Big Paddock, improving transport of goods and firewood and reducing costs. Smaller tramways and walking tracks were later cut through the district.

Chinese miners, first arriving in small numbers in 1866, were working tunnels near the Hau Hau terminus by 1867 and encouraged friends from Otago to join them. Some stayed until the 1920s, with a Chinese market garden and claims still marked on maps as late as 1920.

Dredging technology transformed Westland mining from the 1890s onward. The first dredge at Blue Spur, the Success, operated from 1901 to 1922.

Beyond Gold – Timber, Farming, and Roads

As mining declined, timber milling became a major industry. Mills were built at mine sites to supply timber for fluming and construction, and bush tramways were laid to haul logs to mills and ports. Locally built locomotives hauled timber on these lines.

The cleared land was soon turned to farming. By the late 1870s, newspapers reported “a large area in the vicinity of the Hokitika and Arahura rivers being under cultivation and occupied by a steady industrious class of farmers.” Orchards and crops were planted, and cattle were driven to Arahura’s auction yards.

Farming remains part of Blue Spur’s identity today, with small-scale beef farms, sheep, and goats scattered across the district.

Blue Spur in the Modern Era

By the 1930s, unemployed men were hired during the Depression to extend the Humphreys Gully water race into the Blue Spur goldfield, employing over 100 men.

The late 20th century saw a shift to tourism. A gold-mining attraction opened in 1968, offering visitors the chance to pan for gold and watch demonstrations of historic technology — even attracting famous visitors like Kenny Rogers and the First Edition, who filmed a music video on site.

Today, Blue Spur combines history with lifestyle and recreation. Open-cast mining and dredging still take place, but much of the area has regenerated into lush native bush, popular with hikers and mountain bikers. Accommodation options, from backpackers to boutique lodges, cater to visitors. The Blue Spur Bush Walk guides tourists through the ridge diggings, and the scenic drive from Hokitika to Blue Spur offers a diversion from State Highway 6. Subdivisions at Ballarat Hill, Keogans Road, and Terraceview have brought new residents, many running hobby farms or lifestyle blocks.

From gold rush to farming, milling, and modern tourism, Blue Spur has been shaped by cycles of boom, bust, and renewal. Its story is a microcosm of West Coast histories.